In the middle ages, nursing work was often undertaken by clergy such as monks and nuns.

A perfect example is the Augustinian canons and canonesses who originally staffed St Thomas’ Hospital. Founded in the 12th century, St Thomas’ was Walworth’s local hospital for several hundred years.

The Reformation, in the 1500s, saw the closure of monasteries and convents across northern Europe. In the process, these skilled carers, from the church, were removed from their positions in hospitals and almshouses and their training sites were destroyed.

As a consequence, nursing became the domain of untrained and often unskilled workers right up until the 19th century. Many were widows or former domestic servants who were unable to get any other job. Charles Dickens’ character, Sarah Gamp (from Martin Chuzzlewit) reflects the popular early Victorian stereotype of a nurse as sloppy, incompetent, and often drunk.

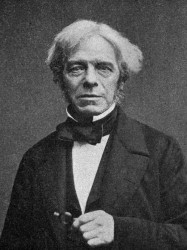

In an era before germ theory and the importance of antiseptic hygiene was understood, hospitals were often dirty places that spread, rather than prevented, disease. This changed in the mid-Victorian period, in large part, due to the Crimean War (1853-6).

The Crimean War was one of the first wars to use modern technology, such as high-explosive shells, railways and telegraphs. But technological advances in health care lagged far behind those on the battlefield. Hospitals were understaffed, the staff were overworked, supplies were short and hygiene was poor. As a result, wounded soldiers faced horrific conditions and infectious disease. Cholera accounted for far more deaths than battle wounds.

It would be women, trained in the pre-Reformation tradition of religious nursing, who stepped into the breech. And one woman in particular.

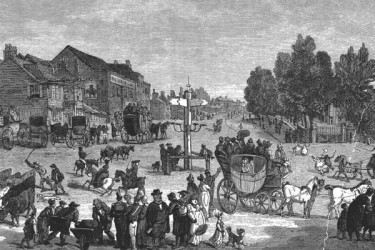

St Thomas’ was Walworth’s local hospital for several hundred years

Florence Nightingale was a wealthy and well-connected British woman. She had studied nursing at a Lutheran religious community in Düsseldorf which trained nurses in the pre-Reformation tradition. She was also a close friend of Sidney Herbert, the chief administrator of the British Army, who requested that she lead a team of nurses to the Crimea to care for the troops.

She arrived in 1856 with 38 volunteers she had trained in Istanbul. These were soon followed by another group of 15 nurses from the Sisters of Mercy convent, Bermondsey. Led by their Mother Superior, Mary Clare Moore, they had been nursing Southwark’s poor at Guy’s and St Thomas’ hospitals since 1839.

Moore took charge of the stores, kitchens and orderlies, and she placed her nuns at Nightingale’s disposal. The two remained close friends until Moore’s death in 1874.

In the Crimea, Nightingale improved hygiene practices (introducing regular handwashing, for example). She collected valuable statistical data and pressured the army to make other improvements. These included the introduction of a prefabricated hospital (designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel) that increased the survival rate of patients thanks to better ventilation and hygiene.

In 1855 the Nightingale Fund was established which raised £45k (equivalent to more than £4m today). Nightingale used this money to open the Nightingale Training School at St Thomas’ Hospital.

It was the first secular nursing school in the world and the oldest one attached to a fully fledged hospital and medical school. It still exists today as the Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery & Palliative Care (now at King’s College London in Waterloo).

Nightingale possibly chose St Thomas’ because of its connection with Mother Mary Clare Moore but also on account of the hospital’s matron, Sarah Wardroper.

Born in 1813, Sarah married a physician, Woodland Wardroper in 1840. Sadly, Woodland died just nine years later, leaving Sarah with four children to support.

Although she had little nursing experience (outside of her family), she had a good general education as well as excellent organisational skills. Possibly combined with some experience gained in her husband’s medical practice, it was enough for Wardroper to be appointed matron of St Thomas’ Hospital in 1854.

At that time, matrons were the most senior nurses in any hospital. They were responsible for overseeing patient care, management of nurses and domestic staff (such as cooks and cleaners) as well as overseeing the budgets.

Nightingale admired Wardroper’s ability and efficiency, describing her as a ‘hospital genius’ and chose her to be the first superintendent of her new training school.

Wardroper was much less interested in nursing education than in cementing nursing as a profession and improving standards. To this end she hosted tours of St Thomas’ Hospital, to showcase professional nursing, and visited other hospitals to professionalise their care.

The original St Thomas’ Hospital was founded in St Thomas Street, Borough.

In 1862 it had to move to make way for the expansion of London Bridge Station. It would eventually relocate to the Albert Embankment, Lambeth, where a new hospital would be built in accordance with Nightingale’s theories on hygiene. In the meantime, St Thomas’ needed a temporary site.

Luckily, the Royal Surrey Gardens in Walworth had closed that same year. This former zoo, music hall and public pleasure garden had more than enough space to host the hospital until the Lambeth site was completed in 1871.

The music hall, alone, could accommodate 100 beds, while the giraffe house became a cholera ward and the elephant house was used for dissections. Nothing remains of the temporary hospital but Pasley Park marks the site today.

Wardroper died in 1892. Her memorial, in the chapel at St Thomas’, was created by the Walworth sculptor, George Tinworth.

More recently, Sarah has been remembered in the name of Wardroper House on St George’s Road, one of the early rehousing schemes built as part of the regeneration of Elephant and Castle.