The Romans felt the threat of restless spirits was too great to allow their dead to lie inside the city. Instead, as the 2018 discovery of an ancient sarcophagus in Harper Road reminded us, the area between Borough and the Elephant was used as a vast Roman necropolis.

In the Elizabethan period, this stretch of Southwark was used for theatres, bearbaiting, prostitution and any other kind of activity considered too disreputable for London proper. In fact, having long existed beyond the bounds of the city’s jurisdiction, the area had earned itself a reputation as somewhere for shady characters to escape the long arm of the law.

Unsurprising then that Newington Causeway, in Elephant and Castle, would come to house a number of London’s gaols. And it made sense to keep prisoners – especially those who had committed crimes against the state – well away from the established seats of power in Whitehall.

Horsemonger Lane Gaol, built between 1791 and 1799, at the junction of Harper Road and Newington Causeway was one of the biggest.

The main gaol for the county of Surrey, it replaced a number of smaller, local prisons (mostly ramshackle, repurposed buildings, a hundred years old or more) including the White Lyon Gaol which stood between Borough High Street and Tennis Street.

Horsemonger Lane is now Harper Road and the gaol was located on the site of the present day Newington Gardens. It was a three-storey quadrangle with three wings for regular criminals and a fourth for debtors.

The gaol’s gallows, where 131 men and 14 women were executed between 1800 and 1877, stood on the roof of the gatehouse.

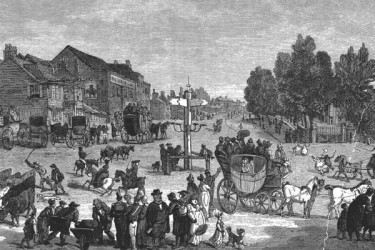

Rooftop gallows enabled public executions

Rooftop gallows enabled executions to take place in public, which the authorities thought would deter crime. Ironically, these gruesome events actually contributed to crime and disorder, especially pickpocketing, since the sheer spectacle of an execution drew enormous crowds.

Horsemonger Lane had a number of famous prisoners.

In 1813, the poet, Leigh Hunt was imprisoned here over a newspaper article he wrote about the Prince Regent; W C Minor (one of the most active contributors to the Oxford English Dictionary) was held in the gaol before his 1872 trial for murder. He was found not guilty by reason of insanity and spent the remainder of his life in Broadmoor. Edward Marcus Despard, a former viceroy of British Honduras, was executed at Horsemonger Lane in 1802.

Despard had already done a spell in prison for debt. He’d also been suspended from office for treating the white colonists and freed black slaves of Honduras equally (even with the abolition of slavery on the horizon, this was still a step too far in the opinion of many in the British establishment). He hatched a plot to incite a popular uprising with a plan to assassinate King George III and seize both the Tower of London and the Bank of England. But, before he could put it into action, he was arrested and tried for treason. His hanging attracted more than 20,000 spectators.

Perhaps the most notorious of all the Horsemonger prisoners, were Maria and Frederick Manning – perpetrators of what became known as the ‘Bermondsey Horror’.

Maria emigrated from Switzerland to England in the early 1840s to work in domestic service. In 1847 she married Frederick Manning, a guard with the Great Western Railway, at St James’s Church, Piccadilly.

Frederick lost his job shortly after the wedding and the couple moved to Taunton where they opened an inn. However, within a couple of years, business at the inn had dried up and they returned to London. By this point, drinking heavily, Frederick was unemployable.

Later that year, the Mannings would be found guilty of the murder of Patrick O’Connor.

O’Connor was what we’d now describe as a tax-collector and was one of Maria’s former suitors. On top the income from his day job, O’Connor had grown wealthy through some lucrative, albeit criminal, sidelines, including smuggling and usury (lending money at extortionate rates).

On 9 August 1849, Maria asked O’Connor to dinner at their Bermondsey home, where she and her husband shot him and beat him with a crowbar. They buried his body under the flagstones of their kitchen before Maria broke into O’Connor’s lodgings and stole cash, stock certificates and letters she had written to him. She fled to Edinburgh with most of the loot, while Frederick fled to Jersey.

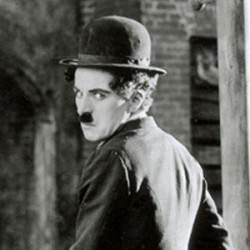

Charles Dickens was amongst the spectators

They were soon caught and were both tried in October of the same year. They were executed at Horsemonger Lane on 13 November – the first husband-and-wife execution for decades and one of the last public executions in Britain. It drew a crowd of around 40,000 people (in which one person was crushed to death and two more injured) and printers produced 2.5 million broadsheets (newspapers) featuring lurid details of the crime.

Charles Dickens was amongst the spectators that day. He later wrote a scathing letter to The Times, criticising the practice:

“I am solemnly convinced that nothing that ingenuity could devise to be done in this city, in the same compass of time, could work such ruin as one public execution, and I stand astounded and appalled by the wickedness it exhibits. I do not believe that any community can prosper where such a scene of horror and demoralization as was enacted this morning outside Horsemonger-lane Gaol is presented at the very doors of good citizens, and is passed by, unknown or forgotten.”

The protests of Dickens and many others eventually led to change and Britain’s last public execution was in 1868.

Today, Newington Causeway continues to play a major role in the British judicial system. It is now home to the Inner London Crown Court, located just a few feet from where the Horsemonger Lane Gaol once stood.