Born in 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft is celebrated as one of the intellectual founders of feminism. By the age of 18 she was living, on and off, in what we now think of as Elephant and Castle.

Her story, and her thought, owes much to the titanic changes that were rocking society in the 18th century; specifically the ideals of the American and French Revolutions. On a local level, Walworth was also going through rapid changes of its own. Understanding these changes helps us to shine a little light on Wollstonecraft’s world.

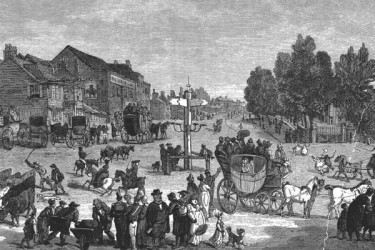

Traditionally, Walworth had been a farming village. It supplied crops for the London market and it provided coaching inns for travellers to and from the capital. The 1629 book, Paradisus Terrestris, praised the quality of the area’s Newington peaches, which ripened at the end of August. At this time, the land on either side of Walworth Road was still common farmland, parcelled out on a yearly basis.

John Rocque’s 1746 map of London and Southwark marks two windmills in Walworth and there was still a manorial court for the area and even a manor house (which stood at the corner of Penton Place and Manor Place). By this time, the area surrounding what we’d now call the Elephant and Castle junction was already relatively built-up and home to important buildings like the parish church and school (both roughly where the Castle Centre stands today).

Walworth was growing in status and it was already starting to attract more middle class families just like the Wollstonecrafts. As London’s roads and transport improved, the pace of change in the area began to increase too.

Since mediaeval times, a huge proportion of London’s traffic had used Newington Causeway as the route to London Bridge. Right up until the 18th century, the next nearest place to cross the Thames was at Staines. It wasn’t until Westminster Bridge opened in 1750 (soon followed by Blackfriars Bridge in 1769) that regular commuting became practical. At this point, the area’s enviable transport links cemented its position as an attractive and convenient place to live, just as it is today.

Walworth was an ideal area for the Wolstonecrafts to settle

As the century progressed, Walworth and its environs became increasingly fashionable and new housing developments began to spring-up alongside market gardens. Surrey Square, which still stands today, is just one example. Penton Place followed soon afterwards along with several new schools.

Walworth had ‘arrived’. It was now a genteel place – one that combined traditional market gardening with upward mobility and a modern education. It was an ideal area for the Wollstonecrafts to settle.

Mary Wollstonecraft’s father, Edward, was a drinker and a bully who dreamt of leaving the family silk weaving firm behind to become a gentleman farmer. As a consequence, he was constantly uprooting his wife, Elizabeth, and their six children.

The family bounced from London to Epping and from Yorkshire to Wales as Edward tried his luck at farming. Each move saw the family progressively worse off and meant that Edward’s eldest son, Ned, was his only child to receive systematic schooling. Mary spent enough time in a Yorkshire day school to learn to read and write, but no more.

Edward’s treatment of his wife and children, and particularly the negative way in which Mary’s cleverness, curiosity, and forcefulness were received (especially in comparison to her brother) sowed the seeds for what would become her life’s defining work: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published in 1792.

In 1775, a mutual friend introduced Mary to Fanny Blood. Fanny was slightly older than Mary and helped to guide her intellectual awakening. Moreover, Fanny lived with her widowed mother and provided a potent role model as an independent woman. Fanny would become the emotional centre of Mary’s life for the next decade.

The Bloods lived in Newington Butts and the prospect of living near to her beloved friend gave Mary the impetus to press for another family move. In 1777 she persuaded her father to uproot again – this time to try his hand at gentlemanly market gardening in Walworth.

But even living close to her dearest friend wasn’t enough to make Mary’s home life tolerable and she soon made an attempt to leave and earn her own living somewhere else.

In an effort to keep her close, her mother found Mary lodgings elsewhere in Walworth. This was at the home of philosopher and translator, Thomas Taylor in Manor Place. Taylor acted as a tutor to his new lodger and undoubtedly influenced Mary in her own philosophical works. By 1778, Mary was working as Taylor’s paid companion but she would return to live with the Blood family after her mother’s death in 1782.

It’s the Taylor connection, which probably accounts for one of the Cuming Museum’s prized artefacts – a small card signed by Mary herself. It belonged to the museum’s founder, Richard Cuming Jr, who grew up at 3 Dean’s Row (now 196 Walworth Road) just around the corner from Manor Place. It’s quite possible that Mary used it as a calling card to announce herself to her new neighbours, the Cuming family, on a social visit.

Mary Wollstonecraft died at the age of just 38, only eleven days after giving birth to her second daughter (who would become famous, in her own right, as the author of Frankenstein). There are various parts of Walworth that would still feel familiar to Mary today, and it’s pleasing to know that a small token of her time in the neighbourhood still resides in the borough’s very own Cuming Collection.