Elephant and Castle’s local brigade, the 24th Battalion of the London Regiment, was based at what is now Braganza Street, off Kennington Park Road. Of the 1,200 men who left for the Front in April 1915, only 17 were still serving with the battalion when it returned home in May 1919. One of those who died, Leonard Keyworth, is still remembered in the name of a local street and school today.

Originally from Lincoln, Leonard enlisted with the 24th Battalion at the start of the war and went on to win the Victoria Cross. He was recognised for his bravery in capturing and holding a German trench near Givenchy in July 1915.

Tragically, he died of his wounds just three months later. Keyworth Street, which runs through the London South Bank University campus, is named in his honour.

Beyond the 24th Battalion, local men and women served in every branch of the military and every theatre of the war. James Hines, an able seaman in the Navy, survived the sinking of HMS Louis off Gallipoli in 1915. The First Surrey Rifles, a local volunteer unit, fought at High Wood (near Ypres) in August 1916. Only two officers and 60 soldiers survived. Winnifred Hawkins, a local nurse, received the Military Medal for her actions during an air raid on a casualty clearing station in Belgium.

For every man and woman at the front, there was a family left behind. The sheer scale of sacrifice made by some can be hard for us to grasp today. Mrs Heard, of Carter Street, was a mother to 17 children and, according to the South London Press at the time, had six sons plus two sons in-law on active service. Five of them were wounded. Another local family, the Patersons, had 11 members on active service as early as 1916.

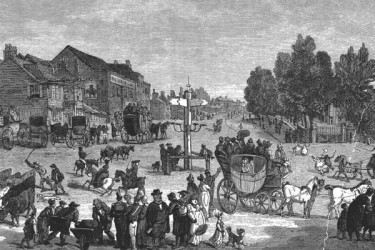

As the war progressed, streets all around the Elephant developed impromptu shrines to the fallen.

On the home front, the war brought opportunity for some and further deprivation for others. Many local women, for example, took on traditionally male jobs at the South London Metropolitan Gas Company, headquartered off the Old Kent Road. Meanwhile some men, employed in what were considered ‘non-war essential’ jobs, were to see their incomes depleted. The Bellamys of Leroy Street suffered when Mr Bellamy’s job in printing was slashed to just three days a week. The family had only 12 ½ shillings a week to feed, clothe and care for a household of eight. It wasn’t enough. In December 1914, the Southwark coroner’s court ruled that their baby daughter Ruby’s death from pneumonia was linked to malnutrition.

Out of 29 bombing raids on London, 12 involved Southwark

Food price rises hit poorer areas such as the Elephant especially hard, particularly as the advent of submarine warfare cut off food supplies from abroad. Rationing began in February 1917, albeit on a voluntary basis to start with. Both central and local government asked people to do more with less and the Metropolitan Borough of Southwark held cooking demonstrations to show people how to make the most of their meagre rations.

Perhaps the most frightening new development on the home front came from air raids. The Germans bombed London with both Gotha bombers and Zeppelins. Out of 29 bombing raids on London, 12 involved Southwark. A daylight raid on 13 June 1917 killed six and injured 12 and a further Zeppelin raid in October brought the total dead to 24.

A local coroner noted that two things had made the casualties worse; the fact that the public was not routinely warned about air raids and the fact that people (perhaps because of the sheer novelty of seeing an aeroplane or blimp) tended to stand and stare at the bombers rather than take cover.

Even a century on we still have much to discover about how the First World War changed our borough and the lives of those associated with the area.

You can find out more about the war in London at the new First World War galleries at the Imperial War Museum.